|

Preface Preface

This book has a

resemblance to my Art & Science of Wild Turkey Hunting

published in 1989 because I have retained from it some of the photos and a

few of my favorite turkey hunting anecdotes, but more has been added than

retained and the retained parts have been completely re-written and

up-dated.

Added material

includes parts of two of my out-of-print books—

The Voice and Vocabulary of the Wild Turkey

and Managing wild turkeys in Florida. I have added topics

from After the Hunt with

Lovett Williams including a chapter on how to make and use a

wingbone yelper, and a new chapter on the Gould’s wild turkey based on

my work in the Sierra Madre Occidental of Mexico since 1989. There is also

an account of the origin of the Merriam’s wild turkey which I was not

aware of when The Art & Science was written. There are also

different color illustrations and updated and corrected maps of the wild

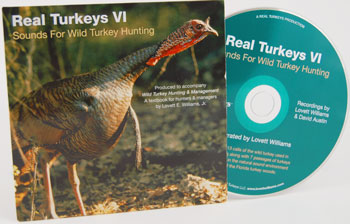

turkey’s distribution. The compact disk inside the back cover, which is

new, presents narrated audio recordings of the calls used in turkey

hunting and in calling contests as discussed in the text.

The term management

in the title reflects an increased emphasis in the present edition on

managing wild turkeys on private land. The advice I offer is based on what

I have learned in 50 years of observing, studying, and managing wild

turkeys and other wildlife. The focus is on practices to maximize wild

turkey numbers but I know that many managers do not wish to go to that

extreme. Managers must decide for themselves how much effort and budget

can be assigned to wild turkeys and most will prefer to “optimize”

turkey numbers rather than “maximize” them.

Some practices

used in managing wild turkey populations are helpful to other wildlife but

some are not. No land management practice fits all wild species. To insure

balance, land managers would benefit from the assistance of a trained and

experienced wildlife consultant in drawing up a management plan. The free

advice that so abounds in popular publications about wildlife management

is worth exactly what it costs.

My management

recommendations are heavily flavored with ecological principles. I do not

go deeply into agricultural and animal husbandry approaches because they

are untested substitutes for the turkey’s real needs. The wild turkey is

well suited for life in the natural environment of North America where it

evolved. Planted food crops can only supplement what Nature has always

provided. It took natural processes millions of years to bring the turkey

to where it is today and the best we can do to enhance its well being is

to work effectively with Nature. I will attempt to explain how to do that.

Another theme

is about how to become a more successful turkey hunter. My goal is to

encourage better hunting skills because skill leads to greater hunting

success and to greater appreciation of the wild turkey and the great

outdoors. Appreciation of wildlife and nature is the fuel of conservation.

My studies of

the wild turkey have been mostly in my native state of Florida where

eastern and Florida turkey populations meet. Museum taxonomists named

certain wild turkey populations as “subspecies” during an era when

zoologists believed that subspecies were “mini” species in line to

evolve over time into bona fide species of their own. Zoologists

have since abandoned the naming of new subspecies because of its false

implications. The forum on subspecies of birds published in the journal of

the American Ornithologists’ Union (see Weins, 1982 in Literature Cited)

explains the present lack of scientific interest in subspecies

designations and should be mandatory reading for all professional wildlife

people. Continued use of subspecies names in professional writing only

sustains out-dated concepts.

Although

today’s ornithologists have little interest in subspecies, I use five

subspecific names in referencing geographic populations because the names

are useful labels in describing the slams of wild turkey hunting and, in

that regard we are, after all, dealing with sport, not science.

Literature

citations and footnotes are used in scholarly books so that readers can

evaluate the validity of ideas presented and to credit other researchers

and writers. I have cited sources but only sparingly because citations are

distracting to the reader and I don’t think important in a book of this

type. I hope no biologist or writer is offended.

I make

frequent use of the adverbs usually, almost, normally, mostly, rarely,

frequently, and modifying phrases like most likely because I

do not know enough about turkeys to use terms such as never and always.

Besides, I am not sure there is anything that turkeys always or never do.

I have limited

the book to what I know. The literature discussed in the Chapter 11 and

listed in Literature Cited can put the reader on the trail to all that has

been written about the wild turkey. But I would caution that not all that

has been written is true. A book bigger than all those combined would be

needed to describe what is not known. When you read, do so with caution,

consider the source, and realize that truth has to be discovered--it

cannot be created.

As more is

learned about the wild turkey, some of my interpretations will be improved

upon and some rejected. That’s the way we make progress. Meanwhile, if

you find errors in Wild turkey hunting and management, please

forgive me and if I am still around and you can find me, bring them to my

attention so I won't make the same mistakes again.

I have had a

lot of help with my wild turkey studies over the years as you will see

from a glance at the Acknowledgements, but any errors you find I made all

by myself.

Lovett E. Williams, Jr.

Cedar Key, Florida

Dust Jacket

|

PLUS

PLUS

Preface

Preface